Usefulness of Agentic Coding and the Novelty Spectrum

A common argument in discussions about agentic coding tools goes something like this: AI is great at generating code that’s been written a thousand times before, but once you ask it to solve something “new,” the quality drops off fast. That sounds reasonable at first, but it’s also a bit hand-wavy. What does “new” actually mean when we talk about writing software?

When developers solve problems, we rarely invent things from scratch. Most of the work is pulling from a mental library of patterns we’ve picked up over time and combining them under a specific set of constraints. The real skill is not so much knowing the individual patterns, it’s about knowing how to compose them, adapt them, and deal with edge cases that don’t quite fit. As constraints get weirder or more specific, the problem gets more interesting and that’s usually where experience and creativity starts to matter.

So how often do engineers work on truly novel problems? Not that often, at least if “novel” means inventing a new algorithm or exploring an entirely new problem class. That kind of work mostly shows up in research-heavy settings, like mathematics or scientific computing. Even there, the hard part is usually the problem definition and the reasoning behind a solution; the code is often just a vehicle for testing ideas. Most developers in production environments don’t live in that world day to day.

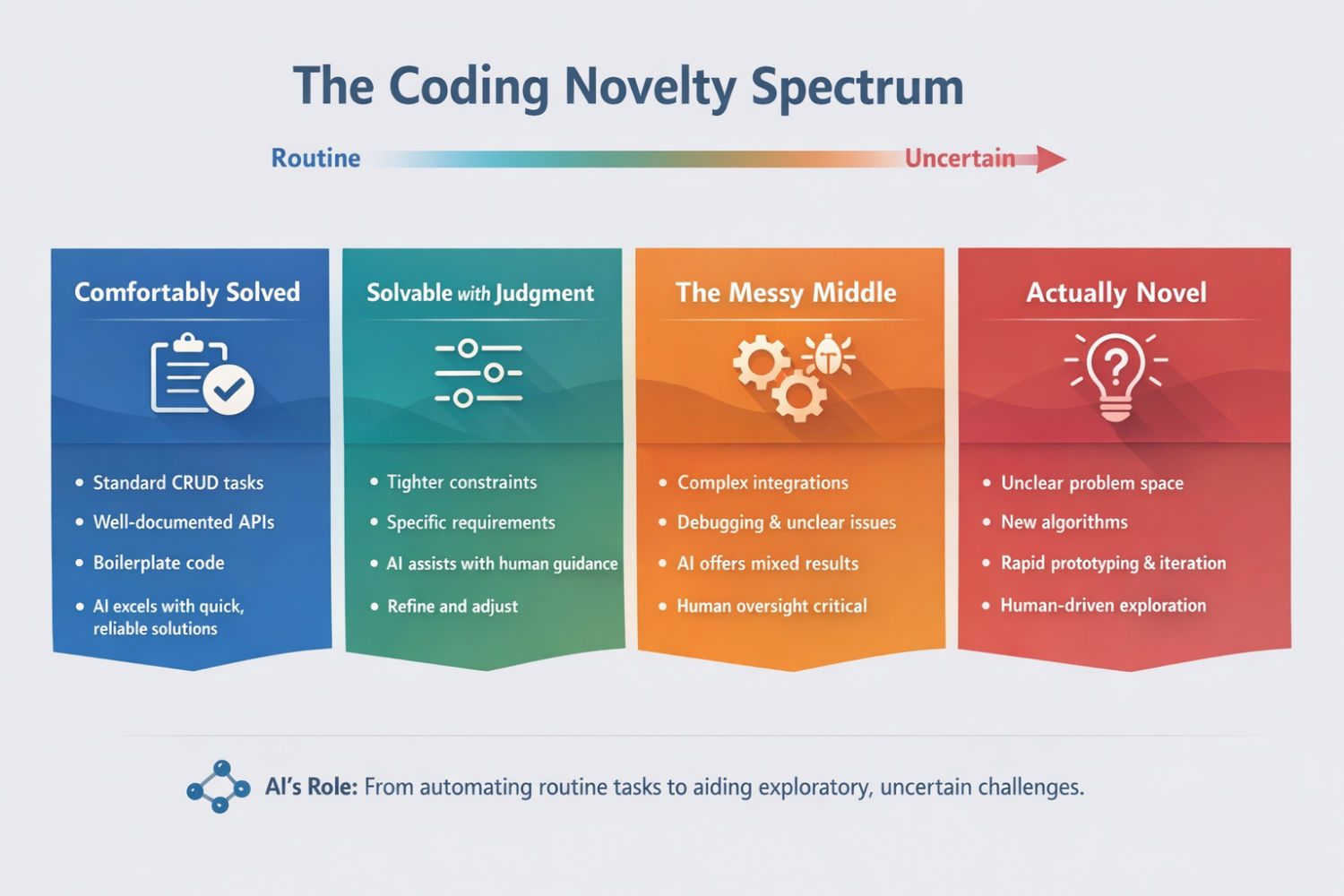

Instead of treating code as either “routine” or “novel,” it’s more useful to think of a spectrum and to look at how agentic coding tools behave across it.

A rough spectrum of novelty#

Comfortably solved

This is the land of standard CRUD apps, well-documented APIs and integrations, boilerplate setup, and problems that Google (or Stack Overflow) has answered a hundred times already. AI models are extremely strong here. They’re fast, consistent, and usually correct. For many business applications, this is still a huge chunk of the work and, honestly, often the least interesting part for experienced developers.

Solvable with judgment

Same basic patterns, but with tighter constraints. Non-functional requirements, edge cases, performance concerns, or domain-specific rules start to matter. AI still performs well, but it benefits from guidance. You nudge it, correct assumptions, and steer it toward a solution. At this point, you’re collaborating rather than just accepting output.

The messy middle

This is where things start to get unpredictable. Multiple systems interact. Production bugs don’t reproduce cleanly, you have to resort to observabilty. APIs are new, poorly documented, or behave differently than advertised. There are hidden assumptions everywhere. AI can be surprisingly insightful here, and sometimes completely misses the point. Human judgment becomes central, not just to write code, but to decide what problem is actually being solved.

Actually novel

Here the problem space itself is unclear. You’re still negotiating requirements with stakeholders. Success criteria shift as you learn more. Maybe you’re exploring new algorithmic approaches, or maybe you’re applying known ideas in an unfamiliar domain. AI struggles to lead here, but so do humans. Where it still shines is speed: spinning up prototypes, testing variations, and supporting rapid iteration. I often use AI in this zone to implement rough mockups that help clarify what even makes sense to build.

These categories aren’t fixed, and problems slide up and down the spectrum depending on context. A “simple” integration can become messy overnight if assumptions break, and a supposedly novel problem can collapse into something familiar once it’s properly framed.

So where does most professional work live?#

In my experience, the majority of professional coding challenges fall into the first two categories, especially in typical CRUD-heavy business systems. The messy middle is smaller but disproportionately time-consuming. Truly novel work is rarer, and when it appears, it’s usually accompanied by a lot of uncertainty, for humans and AI alike.

That’s why the claim that AI “falls apart” on novel problems is both true and misleading. Yes, models can confidently produce plausible but wrong solutions, especially when constraints are implicit or feedback is weak. But that doesn’t mean they’re useless in those domains. Even in the hardest parts of the spectrum, they can save time, reduce friction, and free you up to focus on the parts that actually require human judgment.

And maybe that’s the big advantage of embracing AI. Not that it replaces engineers in the most creative moments, but that it changes where our energy goes. Less time on repetition and more time on decisions, trade-offs, and understanding what’s worth building in the first place.

I’m curious how this lines up with your own experience, especially in the messy or genuinely novel parts of the work?